It’s not exactly news that the Eurovision voting is based on more than just who sent the best song. Neighbouring countries are often more inclined to vote for one another, or not in the case of Ireland and the United Kingdom. But which countries are most blind to the quality of the songs their favoured nations send?

To explore, I pulled data from data.world which lists the results of every final since 1957, including importantly how many points each country awarded to each participant.

Of course over this time there have been some national reshuffles and many of the countries of today, don’t map neatly to a single historical participant. The only case, I believe, where there is a direct mapping is F.Y.R. Macedonia renaming to Republic of North Macedonia in 2019, but please let me know if I’m missing something. Let’s first fix the data so that North Macedonia is named consistently, and no longer existing countries can be filtered out. I’ve also filtered the data to only consider the finals votes.

library(tidyverse)

remove_countries <- c(

"Rest of the world",

"Rest of the World",

"Serbia & Montenegro",

"Yugoslavia",

)

results_df %>%

mutate(

to_country = case_when(

to_country == 'F.Y.R. Macedonia' ~ 'North Macedonia',

TRUE ~ to_country

),

from_country = case_when(

from_country == 'F.Y.R. Macedonia' ~ 'North Macedonia',

TRUE ~ from_country

)

) %>%

filter(

!to_country %in% remove_countries,

!from_country %in% remove_countries,

from_country != to_country,

`(semi-)_final` == 'f',

)

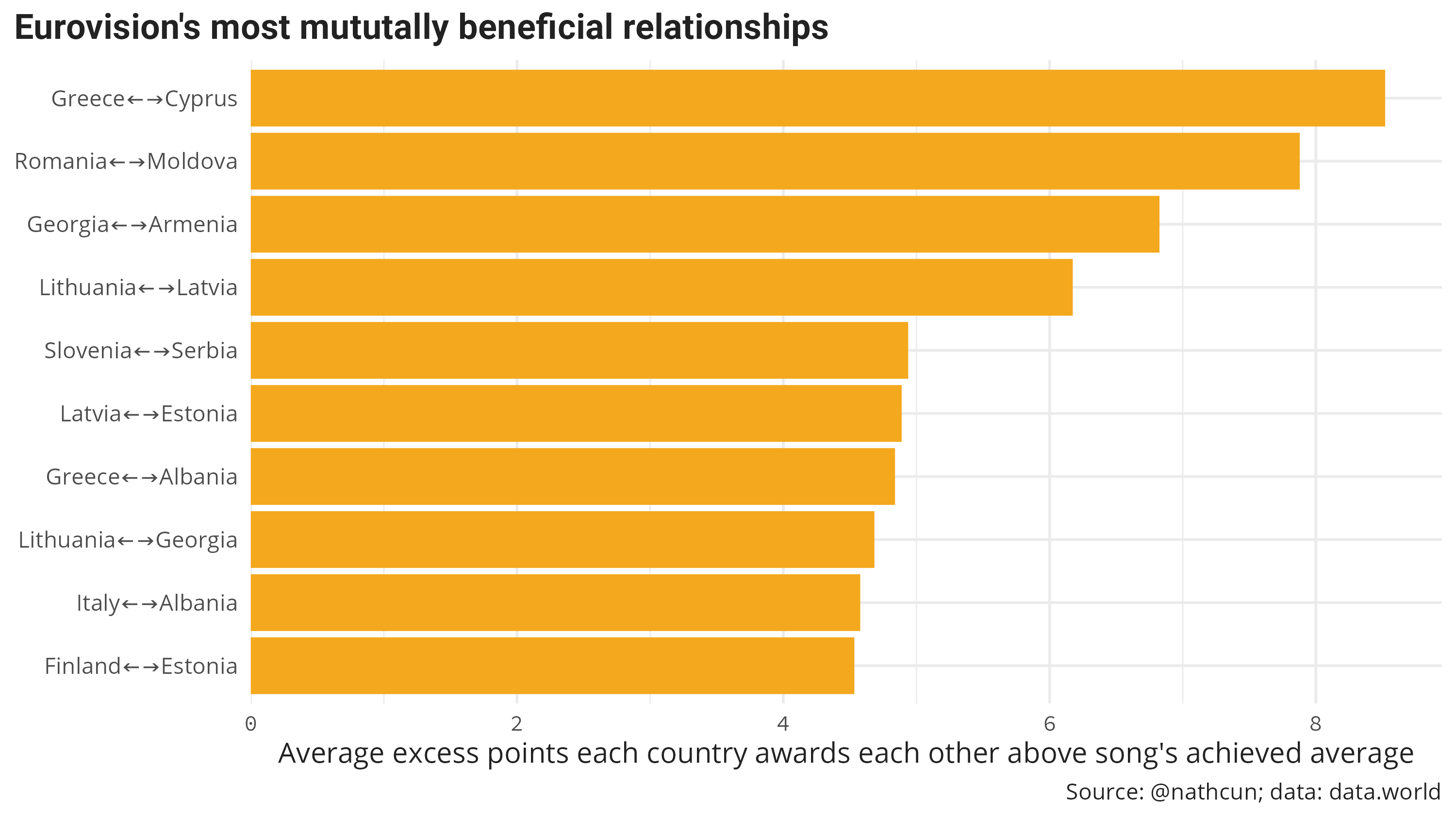

At this point, we can begin to look at which countries have the most mutually beneficial/adversarial relationships. In order to identify a special relationship between countries I considering only the boost in points that countries can expect above and beyond what their song was otherwise worth. Otherwise, we may see that, e.g., Sweden/Ireland have a special relationship with many countries when in reality they’ve just won more times than others.

To do this I calculated the average points received by each country in each participating year, then for each (giver, receiver) pair calculated what the average difference was, as below:

differential_df <- results_df %>%

group_by(to_country, year) %>%

mutate(year_received_mean = mean(points),

differential = points - year_received_mean) %>%

group_by(from_country, to_country) %>%

summarise(

mean_differential = mean(differential)

)

Looking at the top ten pairs, Greece and Cyprus are well in the lead awarding each other, on average, an incredible eight points above what their song was deemed worth by the remaining nations. Elsewhere, the buddies are relatively unsurprising with neighbouring countries often being more generous with their votes.

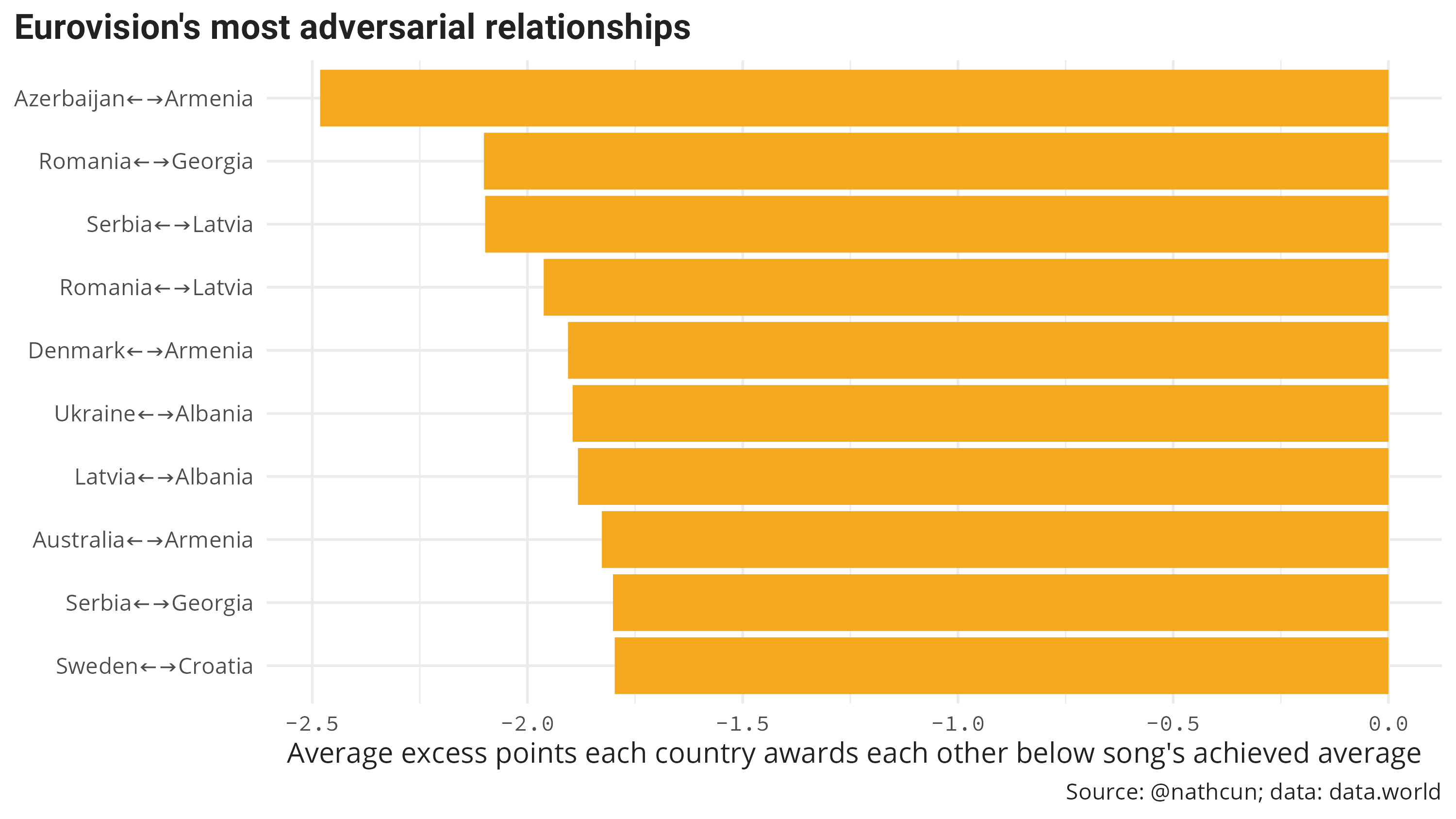

As for the most adversarial nation pairs, the effect is much smaller with Azerbaijan and Armenia only short changing each other by just shy of 2.5 points of their song’s worths. While there are similar geographic relationships here too, there are some others I can’t say I understand. Sweden and Croatia?

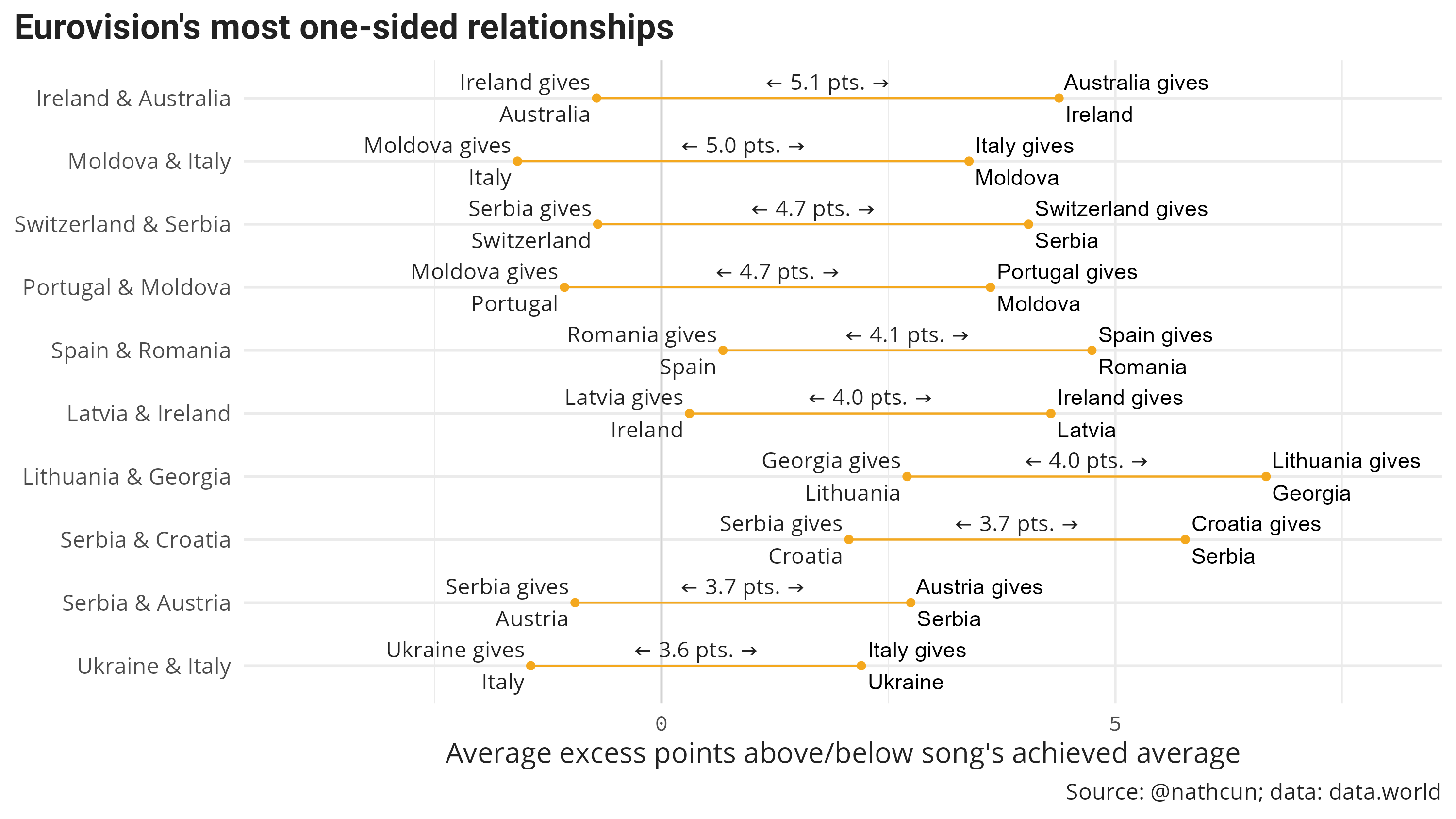

In many cases, the positive relationships between neighbouring countries is due to migration between the two nations, with emigrants then voting for their home nation in their adopted home. However, this flux doesn’t always go both ways, and this can be seen to an extent in the most one-sided relationships.

Ireland has for many years had a large number of emigrants to Australia, but relatively few in the other direction, which would explain why the Australians are so generous towards us while we largely give them what their song is worth. It should be noted, however, that during Australia’s Eurovision participation Ireland have only yet managed to qualify for the final one time.